MixingLab Research

Fluid and solute transport in the brain

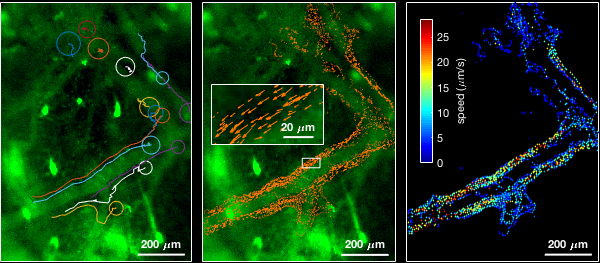

Mammals' brains contain not only blood vessels to bring nutrients and oxygen, but also a separate set of fluid passageways that clear waste and deliver nutrients, collectively called the “glymphatic” system. The system is important for human health, since waste buildup is linked to diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, and fluid misdirected during stroke or traumatic brain injury can cause dangerous swelling. We use experiments and simulations to address an array of open questions: What mechanisms pump away waste? Where does it go? How do sleep, exercise, and age affect waste evacuation? In one project, we focused on links between glymphatic malfunction and Alzheimer's disease, which is known to correlate with waste buildup. In another, we focused on links between glymphatic function and cognition, to help soldiers stay alert even when sleep-deprived. In another, we apply physics-informed machine learning to infer quantities that cannot be measured directly. We are grateful for support for this work through grants from the National Institutes for Health, the Army Research Laboratories, and the Emerging Mathematics in Biology program of the National Science Foundation.

Above: Flow in the glymphatic system of the brain of a live mouse, measured with particle tracking. Left: The measured paths of particles flowing through the brain extend much further than the distances they would travel by diffusion alone (indicated with circles). Center: Each arrow indicates the position and velocity of one tracked particle. Waste flows through the space surrounding an artery. Right: Each dot indicates the speed of one tracked particle (in color).

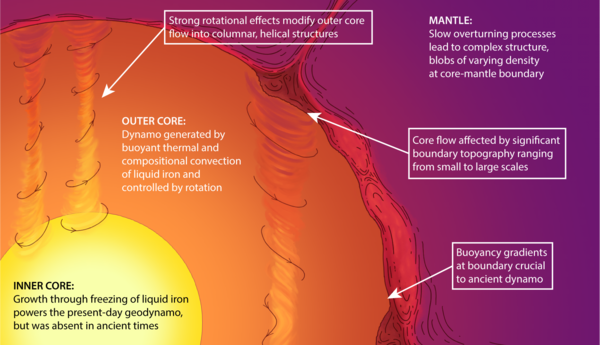

Above: Roughness at Earth's core-mantle boundary may perturb convective flows and enable magnetic field generation via columnar structures, inertial modes, and plumes.

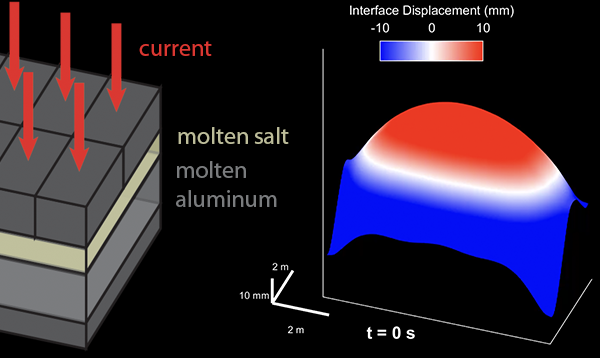

Above: Layers of molten salt and molten aluminum in a smelter can be disrupted by the metal pad instability, as shown by the deformation of their interface (at right). Preventing disruption would improve efficiency and save tremendous amounts of energy.

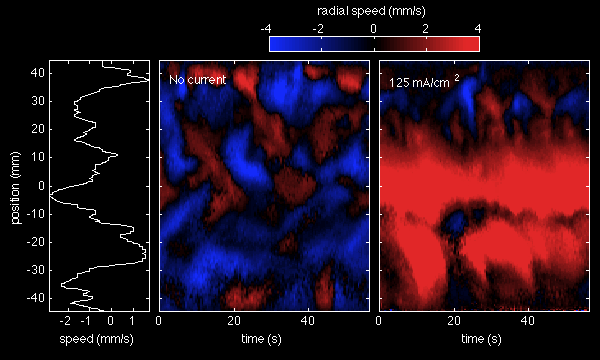

Above: Fluid flow in a liquid metal electrode, measured with ultrasound. Reds indicate flow away from the probe, and blues indicate flow toward it. Adding electrical current causes a global rearrangement of the convection pattern and makes mixing more efficient.

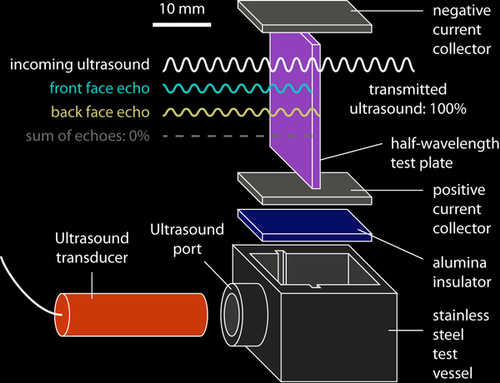

Above: Our apparatus to enable ultrasound in metals casting allows us to apply sophisticated surface treatments to test plates, so that ultrasound passes through them easily and high-precision measurements become possible.

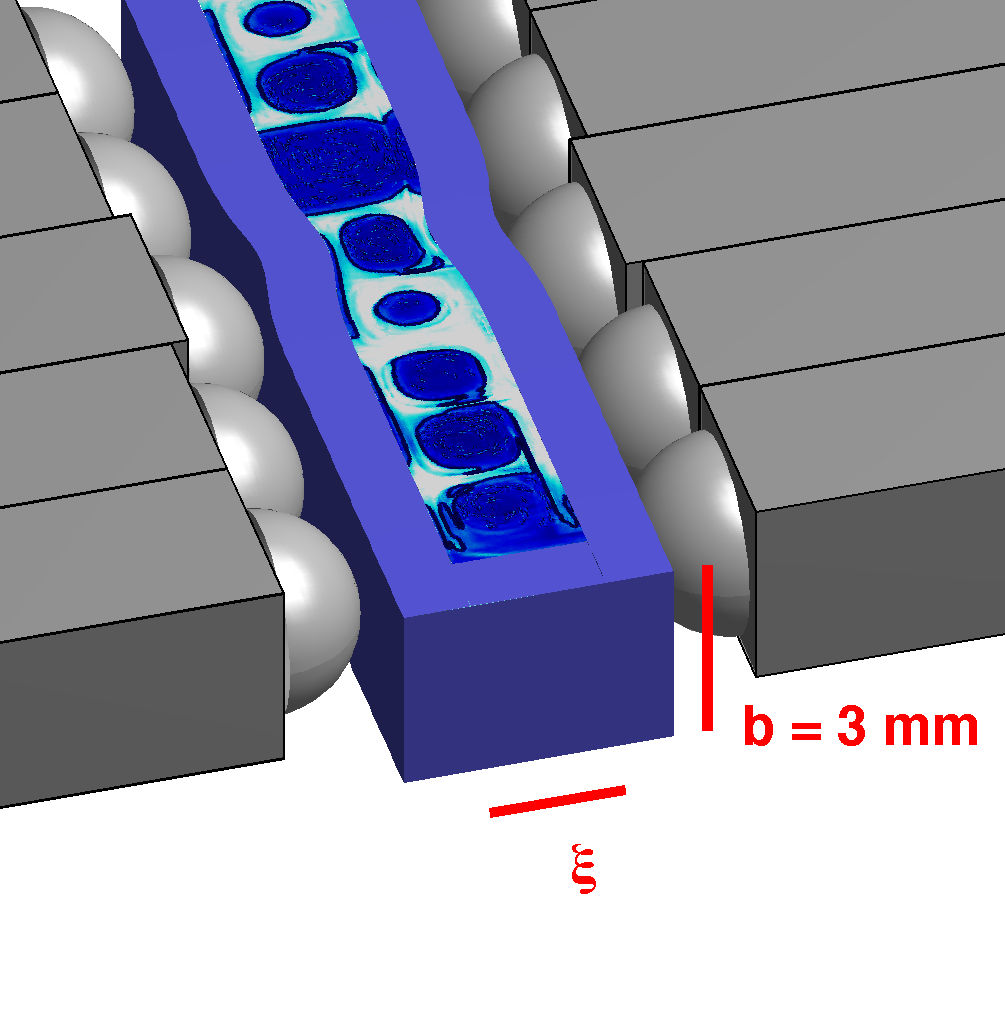

Above: This experimental device will test our hypothesis that peristaltic motions can keep chambers within the mammalian cochlea well-mixed, in order to enable the silent current of ions that enables the cochlea's exquisite sensitivity.

Fluid mixing of dye or other passive materials is complicated, but fairly well-studied. We are pushing further, to study mixing of materials that also react (or grow) at the same time. One important application is ocean flows, where growing plankton are mixed by currents and chemical spills react away as they are swept along.

Above: The Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction causes a color change that spreads over time, even in stagnant fluid. Here we've used image processing to draw black curves along reaction fronts in a movie of a laboratory experiment, sped up by a factor of 25. We use B-Z to study reaction and growth in fluid flows.

To simplify the dizzyingly complex process of fluid mixing, scientists have long dreamed of “coherent structures”, regions or boundaries in the flow that could be tracked over time and would give a simplified—but still powerful—description of the mixing process. We work on this problem by considering Lagrangian Coherent Structures (LCS), clusters of tracer particles (multi-point correlators), and stretching and folding.

Above: In turbulence, Lagrangian Coherent Structures separate regions where energy is transferred to smaller length scales, from regions where energy is transferred to larger length scales. This movie shows LCS (white curves) and energy flux (reds and blues) calculated from a laboratory experiment and played at 1/5 speed.

Flows in planetary cores

Planets can support life only if they have magnetic fields, which protect organisms from space radiation and shield atmospheres from solar winds. Earth's magnetic field arises out of the swirling motions of its molten iron core and is almost as old as the planet itself. Computer models are able to reproduce today's field ‒ but they fail to reproduce the ancient field that arose before our planet's solid inner core. We wonder if roughness on the core-mantle boundary could have focused the swirling motions and enabled a magnetic field. Working in collaboration with Jonathan S. Cheng at the U.S. Naval Academy, we model those phenomena with experiments in the lab: rotating flow driven by heating and cooling rough-walled boundaries, sometimes using water and sometimes using liquid metal. With three-dimensional particle tracking and ten-probe ultrasound to measure flow, our experiments also give us a window into the fundamental physics of rotating thermal convection. We are grateful for support for this work through a grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

Planets can support life only if they have magnetic fields, which protect organisms from space radiation and shield atmospheres from solar winds. Earth's magnetic field arises out of the swirling motions of its molten iron core and is almost as old as the planet itself. Computer models are able to reproduce today's field ‒ but they fail to reproduce the ancient field that arose before our planet's solid inner core. We wonder if roughness on the core-mantle boundary could have focused the swirling motions and enabled a magnetic field. Working in collaboration with Jonathan S. Cheng at the U.S. Naval Academy, we model those phenomena with experiments in the lab: rotating flow driven by heating and cooling rough-walled boundaries, sometimes using water and sometimes using liquid metal. With three-dimensional particle tracking and ten-probe ultrasound to measure flow, our experiments also give us a window into the fundamental physics of rotating thermal convection. We are grateful for support for this work through a grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

Taming fluid instabilities in aluminum manufacture

Aluminum is manufactured by passing a large electrical current downward through a layer of molten salt, where aluminum ore has been dissolved. The process uses tremendous amounts of energy — 3% of all the world's electricity. Improving its efficiency would save energy, reduce costs, and reduce emissions, but the efficiency is limited by a fluid dynamical disruption, the metal pad instability, which can drive an aluminum smelter out of control. We invented and are developing a method to prevent the instability by adding an oscillation to the current, leading the way to more efficient aluminum manufacture. We are grateful for support for this work through a grant from the Advanced Manufacturing program of the National Science Foundation.

Mixing in liquid metal batteries

We are studying the effects of fluid flow on the performance of liquid metal batteries, a technology being developed by Ambri, Inc. for large-scale energy storage on Earth's electrical grids. More broadly, we are interested in using fluid dynamics and mass transport to revolutionize energy storage technology, improve energy efficiency, and enable widespread use of renewable energy. We are grateful for support for this work through a CAREER Award from the Fluid Dynamics program of the National Science Foundation.

Next-generation casting

More than 90% of U.S. manufactured goods contain cast metal components made with a process involving four steps: melting the metal feedstocks, degassing and controlling chemistry, distributing the melt, and solidifying it in casts. The commercial success and energy efficiency of the entire operation require controlling and predicting product quality while maximizing the rate of casting. Unfortunately, measuring the properties of the melt in-situ is difficult, and to date quality tests occur only after solidification. This project, a collaboration with Antoine Allanore at MIT, aims at providing a new tool to evaluate the melt properties using sound waves at very high frequency (ultrasound). The anticipated results are expected to enable real-time monitoring of casting and lead to new processing methods that will increase the commercial success and energy efficiency of casting. We are grateful for support for this work through a grant from the Materials Engineering and Processing program of the National Science Foundation.

Ion mixing in the inner ear

Incredibly sensitive, the mammalian cochlea can detect sounds more than a million times quieter than loud sounds causing pain. The cochlea gets its energy from a "silent current" of ions constantly leaking from one fluid chamber to another, which can work only if the chambers stay well-mixed. In collaboration with our colleague Jong-Hoon Nam, we hypothesize that molecular diffusion alone cannot keep the chambers mixed; instead, the cochlea stirs the chambers mechanically. We will test the hypothesis with laboratory models to complement Prof. Nam's simulations. We are grateful for support for this work through a grant from the Biomechanics and Mechanobiology program of the National Science Foundation.

Advection, diffusion, and reaction in Earth's oceans

Coherent structures in mixing