Build a better world through engineering

Majors and Minors

From certificates to PhDs, explore the degree program offerings from one of the nation’s top engineering schools.

Learn MoreUndergraduate Education

We prepare students to thrive as problem solvers and act as good stewards of our future.

Learn MoreGraduate Education

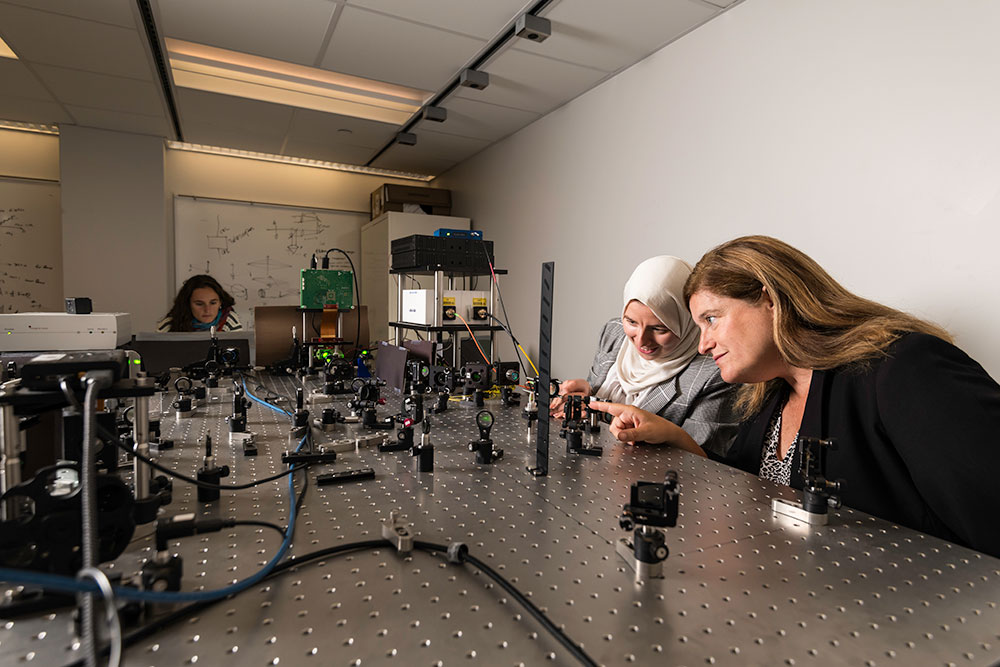

Alongside award-winning faculty, our students use state-of-the-art technology to support their unique and self-driven research and education.

Learn MoreTransformational Research

Across multiple departments and centers, Hajim faculty, students, and staff are developing technological innovations with the capacity to transform our world. Our strong ties and proximity to the University of Rochester Medical Center and the Laboratory for Laser Energetics make opportunities for interdisciplinary research boundless.

Discover our Research CapabilitiesExperiential Learning

Active, experiential learning is at the heart of the Hajim School education. We believe the skills and knowledge you gain outside the classroom are as important as what you learn within it. With endless opportunities through research, study abroad programs, internships, and entrepreneurship, you can pursue your own unique and fulfilling path.

Explore What’s Beyond the ClassroomEngagement and Enrichment

The Hajim School is committed to fostering a dynamic and welcoming academic environment where all students are empowered to excel. Through innovative programs and a culture of respect, the school champions student success, collaboration, and the pursuit of knowledge in engineering and applied sciences.

Find Out Why You Belong HereMeliora

Making the World Ever Better

Engineering is key to solving some of our most difficult societal problems and to developing innovations that will transform society in the years to come.

Our students share how the Hajim School is preparing them to change the world for the better.

Watch on YouTubeHajim Students by the Numbers

The Hajim School is one of the nation’s top engineering schools, housed in a first-rate research University.

27

Hajim School faculty members are NSF CAREER Award winners

2,111

Undergraduate and graduate students enrolled fall 2025

#43

In U.S. News & World Report’s Best Engineering Schools list