Respected and Valued

Innovation and progress in engineering thrive when multiple perspectives come together to solve complex challenges. At the Hajim School, we are committed to fostering an environment where every individual is recognized for their contributions to our academic mission.

Our Goals

While strides have been made in broadening access to engineering education, we continue to focus on attracting and retaining a talented and representative student body, faculty, and staff. To enhance academic engagement and professional growth, the Hajim School has established four long-term objectives:

Community

Cultivate a welcoming and collaborative academic setting that encourages open dialogue and mutual respect across all disciplines.

Visibility

Ensure that contributions from individuals across multiple backgrounds are recognized and celebrated, both historically and in current practice.

Representation

Strive for a learning community reflective of the nation’s broad range of perspectives by strengthening recruitment and retention initiatives.

Leadership

Engage alumni and advisory groups to support mentorship and academic enrichment opportunities that contribute to long-term student success.

Expanding Perspectives in Engineering Our Commitment

Our Commitment

Engineering is fundamentally about solving challenges—many of which shape the future of our world. From climate resilience and infrastructure modernization to cybersecurity advancements and global health solutions, today’s most pressing issues require a breadth of knowledge and creative problem-solving approaches.

To drive meaningful progress, we must ensure that a wide range of perspectives and talents are engaged in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. By fostering an environment where all individuals have the opportunity to contribute, we strengthen the innovation and impact of the field as a whole.

Broadening participation in engineering is not only beneficial—it is essential to advancing solutions that serve society at large.

Letter from the Dean

Overcoming Stereotypes

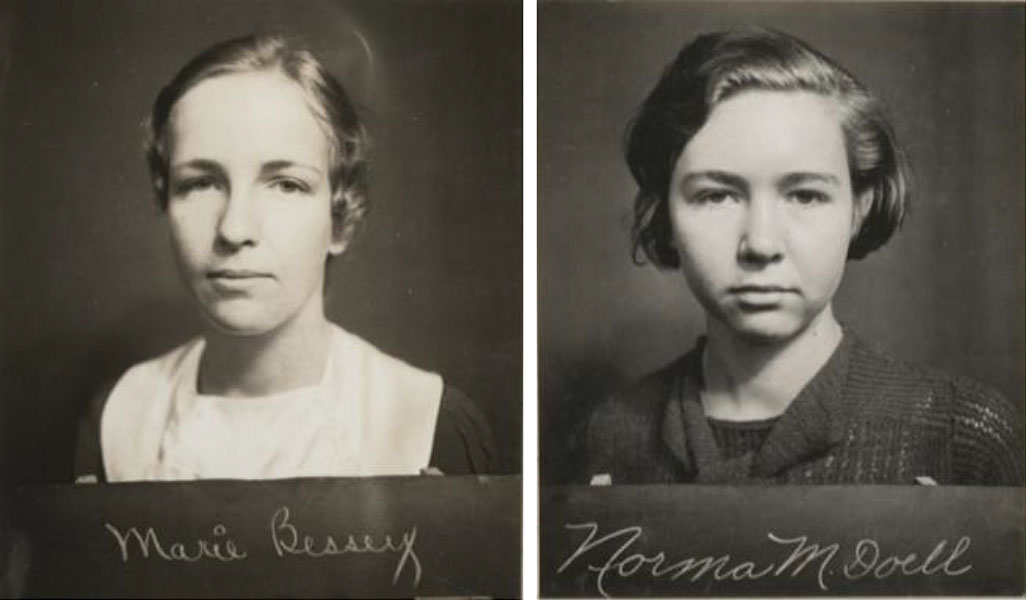

First Women Graduates

Marie Bessey and Norma Doell overcame long-held stereotypes to become the first women to graduate with engineering degrees from the University of Rochester in 1939.

Read More About ThemDiscover Inspiring Leadership

Hajim Spotlights

Explore the stories of more than 50 distinguished faculty, staff, and alumni who have shaped the Hajim School community through their contributions and leadership. Their experiences highlight the ongoing commitment to fostering a welcoming and dynamic academic environment where innovation thrives.

Get Involved

Every member of the Hajim School plays a vital role in fostering an environment of collaboration and excellence. Join us in shaping a learning environment where all individuals can thrive and contribute to meaningful advancements in STEM.

Student Affinity Groups

The Hajim School is proud to support and collaborate with student-led affinity groups that foster professional growth, mentorship, and community engagement. These organizations are open to all students and provide valuable opportunities for students to connect, share experiences, and contribute to an inclusive academic environment.

- Society of Women Engineers (SWE)

- National Society of Black Engineers (NSBE)

- Society of Hispanic Professional Engineers (SHPE)

- Women and Minorities in Computing (WiMC)

- Society of Asian Scientists and Engineers (SASE)

These groups play a vital role in shaping an enriching and supportive learning experience and are for all students at the Hajim School.

Research Experience for Undergraduates

Providing students with early access to research experiences is critical to fostering academic growth and professional development. Through our National Science Foundation-funded Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU) programs, we help broaden participation in research, ensuring that students gain valuable skills and exposure in their academic fields.

These programs equip students with hands-on research opportunities, faculty mentorship, and the tools needed to contribute to meaningful advancements in their disciplines. By leading this effort at the national level, we continue to strengthen pathways for student success in STEM and beyond.

Office of University Engagement and Enrichment

Engaging with the University’s broader initiatives in cultural competence, fairness, and belonging strengthens our academic community and fosters meaningful connections. Rochester’s Office of University Engagement and Enrichment provides exceptional programming, events, and opportunities for collaboration, ensuring that students, faculty, and staff can contribute to an environment where innovation and engagement thrive.