Summertime is prime time for undergraduate research

What’s true for many faculty members is also true for college students. There’s no better time than summer—away from coursework and distractions of the school year—to take a deep dive into research.

The University is home to a robust summer research community that includes Rochester students as well as others from universities across the country who have come here to take advantage of the resources of a tier-one research university that places a high priority on research opportunities for undergraduates.

Rochester is particularly well equipped to deliver research opportunities across multiple disciplines. For example, two new federally funded REU (research experiences for undergraduates) this summer focus on biomedicine and on the computational study of music. They take full advantage of the faculty and resources of the University’s new Goergen Institute for Data Science, its world-renowned Eastman School of Music, and the close proximity of its top-ranked Medical Center to the River Campus.

“We’ve had classes with professors all through our education who have been telling us about their research, and we know they’re doing all these incredible projects, and yet it was just totally under our radar,” says Patrick, a rising senior in mechanical engineering.

“And now we’re involved in this whole other world that this university is so well known for.”

Diving deep into the research experience

- Develop problem-solving skills. Unlike solving a classroom problem, where the answer is known, research is “the process of creating new knowledge, of finding solutions where none are known,” says Wendi Heinzelman, dean of the Hajim School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. “That’s a very different skill from what you get in the classroom,” but one that is critical to almost any career path.

- Decide if research is something they really want to pursue. For many of the students, working in a lab full time can be an eye-opening experience. “You can spend a lot of hours trying to figure things out,” says Graham, a visiting computer science student from the University of Michigan. “After working eight hours some days you feel like you haven’t accomplished much and you begin to wonder if you’re being productive. On the other hand, you are able to decide your own path.”

- Get a head start on applying for graduate school, and start honing the research skills they’ll need when they get there. Many of the students, for example, are benefiting from Graduate Record Exam prep courses offered by the University’s Kearns Center.

An important component of undergraduate summer research is the opportunity to interest first-generation, minority, and female students in pursuing careers in fields where they have been traditionally underrepresented.

Fifteen of the students doing research this summer are McNair Scholars, participating in a two-year Kearns Center program that helps prepare low-income, first generation, and underrepresented minority undergraduates for graduate school. The hope is that they will go on to careers in research and teaching at the university level. (In order to start reaching underrepresented students as early as possible, the Kearns Center’s Upward Bound program also brings high school students from the Rochester City School District to campus each summer.)

“We are never going to solve the issue of lack of diversity in science unless we work earlier in the pipeline,” says Ann Dozier, professor and chair of public health sciences, who is mentoring Nicholas, a McNair Scholar. “The Kearns Center is an important piece of that.”

Seeing a project “actually coming together”

Granted, an eight-week immersion in research is not enough time to change the world. But it can be enough time to make a meaningful contribution to a lab.

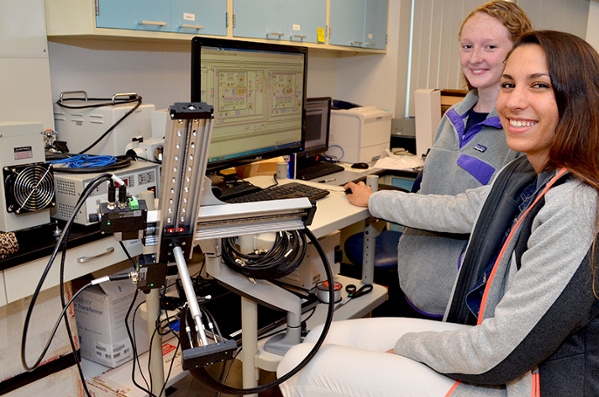

Consider what Amanda Forti ’19, a chemical engineering student at Rochester, and Katelyn Curtis, a mechanical engineering student from Clarkson University, accomplished this summer in the lab of Regine Choe.

Choe, an associate professor of biomedical engineering, is investigating the use of an imaging technique called diffuse optics for breast exams. She assigned the students to work on a device that can automatically direct the probe that is used for the breast exams in a “faster, more repeatable way” than if the probe was held by hand.

Specifically, she asked the students to program a combination of translational stages that serve as the probe’s x- and y-axes, then integrate the two stages with the rest of the device.

Forti and Curtis had to familiarize themselves with Labview—a program language neither had worked with before.

They pulled it off—with two weeks to spare. That left just enough time to do the first of many testings they had hoped to do. “But it was cool to see a project that we spent so many hours working on actually coming together,” Forti says.

“They did a remarkable job,” says Choe.

By the numbers

- 31 Physics, Optics and Astronomy student-researchers; 15 from other universities

- 30 Department of Chemistry student-researchers; 10 of them from other universities.

- 22 Xerox Engineering Research Fellows

- 15 McNair Scholars

- 12 Advancing Human Health REU; 7 from other universities

- 12 Music, Media and Minds REU; 9 from other universities

- 9 Eisenberg Summer Interns (Department of Chemical Engineering)