Teamwork toward a ‘Perfect Bullet’ for Leukemia

Imagine that a drug is “oil” and the human body is “water.” A conduit would be needed to steer cancer drugs through the body to selectively target cancer cells, wherever they reside.

If a budding Wilmot Cancer Institute investigation pans out, a nanoparticle-based delivery system might be exactly the conduit that scientists have been looking for, the trio of young researchers say.

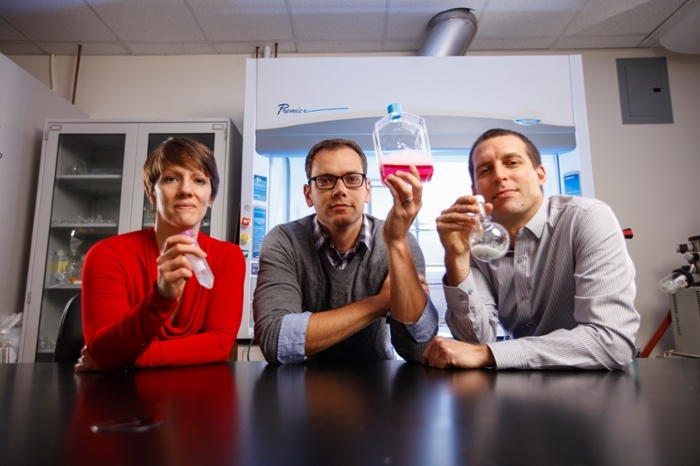

Danielle Benoit, Ph.D., associate professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering, Rudi Fasan, Ph.D., associate professor of Chemistry, and Ben Frisch, Ph.D., a research assistant professor in the Department of Medicine, Hematology/Oncology, are working together to improve the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), one of the deadliest types of blood cancers because it often relapses after initial therapy.

They each bring a different scientific discipline and a distinct role to the project. Fasan develops new drugs and new methods to make them more effective. In this case, he discovered and modified a small-molecule anti-cancer drug derived from a natural plant source related to the magnolia tree. After testing several different chemical forms of the compound, he is studying the correct potency and ability to precisely destroy cancer cells.

Professor Benoit’s nano-delivery system can transcend the barriers that sometimes prevent drugs from reaching their target. Nanoparticles are microscopic materials that act as a bridge between different structures—in this case the nanoparticles are designed to encapsulate an oily drug compound and make it more compatible with the body’s water. Her system also packages the drug with peptides (amino acids) that direct the treatment into the bone marrow, where leukemia takes root.

Getting to the root of the disease is important. Years ago, scientists discovered that leukemia most likely relapses because a subset of cells, known as leukemia stem cells, can dodge standard chemotherapy. Mature leukemia stem cells hide in the bone marrow in a quiet state, until they resurge. Wiping out these stem cells is the key to improving the treatment for a disease that can be very aggressive.

So far, scientists have not been able to target leukemia stem cells directly in the bone marrow, says Frisch, who studies the bone marrow environment for clues as to why blood cancers flourish there. His role is to take Fasan’s new drug, which will be loaded into Benoit’s nano-delivery system, and conduct experiments in cell cultures and mice to find out if the system is effective at binding to cancer cells.

“By using the proper materials to enhance drug delivery,” Benoit adds, “it could potentially revolutionize cancer treatment.”

The team won a 2016-17 University Research Award. Funded annually by UR President Joel Seligman, the money goes to scientists with projects that have a high probability of receiving additional external funding. They received $75,000 to generate data to compete for larger grants from the National Cancer Institute, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, and the Leukemia Research Foundation.

The team won a 2016-17 University Research Award. Funded annually by UR President Joel Seligman, the money goes to scientists with projects that have a high probability of receiving additional external funding. They received $75,000 to generate data to compete for larger grants from the National Cancer Institute, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, and the Leukemia Research Foundation.

“The idea is to have a perfect bullet,” Fasan says. “A very nice feature of this collaboration is that we can take advantage of complementary expertise and run with it.”

This article was originally published in Dialogue, the Wilmot Cancer Institute magazine.